This statue of Captain Cook sits on ‘The Mall’ near the ‘Admiralty Arch’ adjacent to ‘Trafalgar Square’ looking down toward ‘Buckingham Palace’. It occupies, in other words, a key place in celebration of the naval dominance of the British Empire and with a literal direct link to the British crown.

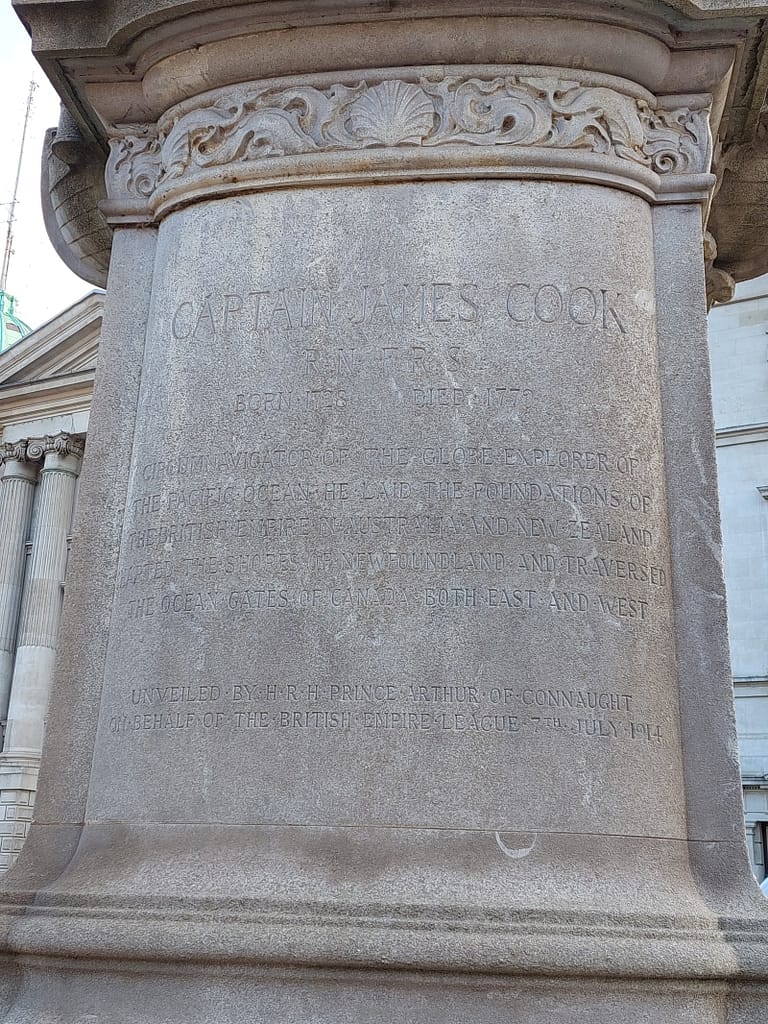

The caption on the plinth reads:

Circumnavigator of the globe, Explorer of the Pacific Ocean, He laid the foundations of the British Empire in Australia and New Zealand. Charted the shores of New Foundland and Traversed the ocean Gates of Canada both East and West. Unveiled by H. R. H. Prince Arthur of Connaught on behalf of the British Empire League 7th July 1914.

The problem here lies not in the telling of history, because Cook is certainly a decisive figure in the history of the western colonial era. No, the problem lies in failing to appreciate that one event in history is not simply a single history, but a meeting point in which multiple histories intersect. For example, Cook did not set the foundations of the British Empire in ‘New Zealand’ and ‘Australia’ because these nations are colonial constructions at the cost of the local peoples and their cultures. The histories in question are those of the British who returned home with fruits of pillage, the local peoples whose lives and histories remain irrevocably changed, and the UK settlers who remained, and whose history belongs not to Europe but also not quite as Second Peoples in a land not of their ancestors.

So, in this ‘memory’ there is a failure to tell the ongoing whole story even while such images are used to romanticise a past for the purposes of advancing a contemporary national identity and culture and which continues narratives of cultural hierarchies (British pride and sovereignty, for example)

But there is a second problem: one of posture and imagined value. The character of the depiction itself, with the confident stride standing on curled rope with a gaze to the horizon, speaks to endeavour and ‘discovery’, the finding of ‘new’ lands (always a surprise to the peoples who had lived there for 1000s of years). It speaks to ideology of “terra nullius” (Latin for “nobody’s land”) and the freedom to possess what one sees.

As G. Bremner suggests, these images

“…communicate a colonial foundation narrative of ‘discovery’, industry, and prosperity in the new world — ‘Australia Felix’.“

Bremner, G., (2020) “Colonial Themes in Stained Glass, Home and Abroad: A Visual Survey”, 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century no. 30, (2020). doi: https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.2900 The full text of this article is available here: https://19.bbk.ac.uk/article/id/2900/

“Australia Felix” means “fortunate Australia”—but—fortunate for whom? The above memory suggests that only one people can rightly answer that question.