Intercultural theology came into existence with the very origins of the faith. Much of the New Testament record is an account of intercultural negotiation and the formation of communities of difference and resulted in significant theological developments, such as the doctrine of justification. Intercultural theology, in other words, is long traditioned way of doing theology. One might argue that such negotiation across cultural difference is the very ground of theological discourse precisely because it is aimed at the formation of communities grounded in the person of Jesus Christ, communities which retain that difference as basic to and a demonstration of their communion. A hard task!

Questions of Context

It is equally the case all theology is contextual theology, both in its formal articulation, in its embodiment or structuring, and in its informal material forms of representation. Despite the type of metaphysical assumptions which can portray the essentially contextual nature of theology as a negative, pretending that some theologies somehow transcend context, there is good theological reason to affirm the contextuality of all theology. As Robert McAfee Brown observes,

There is no way in which a historical faith (one that has received embodiment in specific times and places) could be expressed other than through the cultural norms and patterns in which it is located. If it did not do so, it would fail to communicate. If it did not do so, it would not be historical.

Brown, Robert McAfee. “The Rootedness of All Theology: Context Affects Content.” Christianity and Crisis 37, no. 12 (1977): 170–74, here 170.

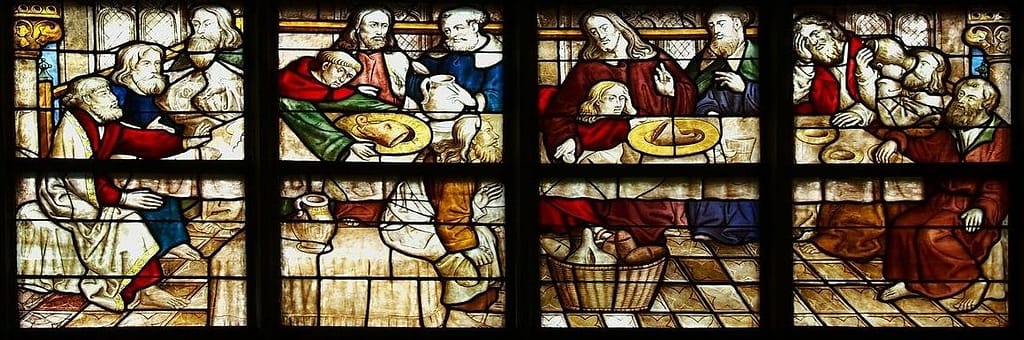

As one example, see the representation of the Last Supper, known as the “Westfälisches Abendmahl,” in the Evangelische Wiesenkirche, Soest, Germany.

A close look at the food enjoyed during this last supper will reveal what is considered “typical Westphalian dishes” including “a pig’s head and ham, rye bread and beer, and schnapps. It is, in other words, a localized vision of the Last Supper. On the one hand, such a local vision establishes some identification between Jesus and the members of that community. But, on the other hand, there is a tension here: to what extent does the presence of pork point to a removal of Jesus’ Jewishness and so one step of many which lead to the events of the 20th century?

As an example of this type of concern, see the “Sermon on the Mount” (1934) painted on the wall of the Autobahnkriche, Brehna, German.

Painted in 1934, the year Adolf Hitler declares himself Führer of Germany, the picture seems to include older soldiers in the bottom right hand corner bearing WWI uniforms. In the middle are two children who seem to be wearing Hitler youth uniforms, with the remainder of the people part of the Volk, i.e., a visualization of blood and soil. A problematic image, of which not much seems to be written. It survived into the present, as I understand it, because after WWII Brehna became part of East Germany and the Communist regime retained the painting as indicating the malfeasance of religion. With the unification of Germany, the painting was heritage listed due to its historical significance. It does mean, however, that the local congregation must gather underneath that image as a constant reminder of its own history.

The community’s commentary on the image states:

“In 1934 a painting was created here on thin plaster that depicts the ‘Sermon on the Mount’. Unfortunately, the Leipzig painter Arthur Manger allowed himself to be influenced too much by the zeitgeist of the time and depicts the figures with questionable military attributes. This depiction contradicts the basic message of the Sermon on the Mount and is in no way shared by today’s congregation.”

https://www.pfarrbereich-sandersdorf-brehna.de/autobahnkirche/die-kirche.html

And the singular image of the painting on the church’s website sets it behind a crucifix as a form of retelling.

This problematic example represents well key suspicions concerning the possible cultural captivity of the gospel when context becomes the focus.

To continue with Brown, however, he rejects the idea that it is “wrong to conceive of theology as contextually conditioned,” arguing instead that the failure to acknowledge the contextual nature of our own theology results in a gatekeeping stance whereby we evaluate theologies “contaminated by cultural importations” against our own “true” theological positions. The above problematic contextualization, in other words, occurs not as a consequence of a focus on context, but a norming which sets a ‘true’ local representation against a ‘them’.

Recognizing the contextual nature of our own theology, in other words, affords space for needed self-critique. Such self-critique may not prevent the above form of cultural accommodation, but it may afford a humility that is basic to such prevention (imagine praying and celebrating communion under that image each Sunday!). Such critique occurs not simply as a black and white binary of acceptance or rejection, but though an extended lived process centered in communion. In this sense, and contra an assumption which seems to drive ecumenical discourse, communion is the assumed framing beginning point and not the ending culmination of another process.

Learning the Lessons

But this story is included here for a second reason, one informing the development of ‘intercultural theology’ as form of formal theological reflection. Or, it is precisely due to the apparent complicity between the Christian faith and German cultural narratives, culminating in two world wars, that German missiologists during the post-war period began to set questions of context in a hermeneutical key.

For a detailed examination of this development, see: Flett, John G., and Henning Wrogemann. Questions of Context: Reading a Century of German Mission Theology. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2020.

Or this YouTube discussion